Helping pays off: People who care for others live longer

Study investigates the relationship between caregiving and lifespan

Older people who help and support others live longer. These are the findings of a study published in the journal Evolution and Human Behavior, conducted by researchers from the University of Basel, Edith Cowan University, the University of Western Australia, the Humboldt University of Berlin, and the Max Planck Institute for Human Development in Berlin.

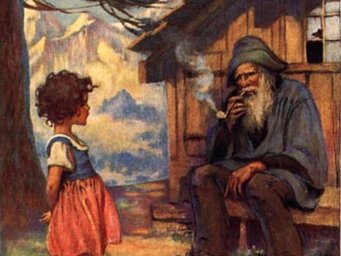

Older people who help and support others are also doing themselves a favor. An international research team has found that grandparents who care for their grandchildren on average live longer than grandparents who do not. The researchers conducted survival analyses of over 500 people aged between 70 and 103 years, drawing on data from the Berlin Aging Study collected between 1990 and 2009.

In contrast to most previous studies on the topic, the researchers deliberately did not include grandparents who were primary or custodial caregivers. Instead, they compared grandparents who provided occasional childcare with grandparents who did not, as well as with older adults who did not have children or grandchildren but who provided care for others in their social network.

The results of their analyses show that this kind of caregiving can have a positive effect on the mortality of the carers. Half of the grandparents who took care of their grandchildren were still alive about ten years after the first interview in 1990. The same applied to participants who did not have grandchildren, but who supported their children—for example, by helping with housework. In contrast, about half of those who did not help others died within five years.

No panacea for a longer life

The researchers were also able to show that this positive effect of caregiving on mortality was not limited to help and caregiving within the family. The data analysis showed that childless older adults who provided others with emotional support, for example, also benefited. Half of these helpers lived for another seven years, whereas non-helpers on average lived for only another four years.

“But helping shouldn’t be misunderstood as a panacea for a longer life,” says Ralph Hertwig, Director of the Center for Adaptive Rationality at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development. “A moderate level of caregiving involvement does seem to have positive effects on health. But previous studies have shown that more intense involvement causes stress, which has negative effects on physical and mental health,” says Hertwig. As it is not customary for grandparents in Germany to take custodial care of their grandchildren, primary and custodial caregivers were not included in the analyses.

The researchers think that prosocial behavior was originally rooted in the family. “It seems plausible that the development of parents’ and grandparents’ prosocial behavior toward their kin left its imprint on the human body in terms of a neural and hormonal system that subsequently laid the foundation for the evolution of cooperation and altruistic behavior towards non-kin,” says Sonja Hilbrand, doctoral student in the Department of Psychology at the University of Basel.