Leonardo da Vinci: reflected in his library

A new exhibition reconstructs the library of the universal genius

Leonardo da Vinci was a tireless and inquisitive reader. He owned more than 200 books about science and technology as well as literary and religious topics. The new exhibition "Leonardo's Intellectual Cosmos" sheds new light on the artist and engineer, who was also a well-read intellectual and who - more than 500 years after his death - still remains as fascinating as ever. The exhibition is on display at Berlin State Library until 28 June 2021 and was curated by the Museo Galileo in Florence and the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science. Due to the pandemic, the exhibition is not yet accessible on site, but can be experienced completely virtually.

Leonardo da Vinci's life had humble beginnings. Born as the illegitimate son of a 16-year-old family servant in the town of Vinci in Tuscany on 15 April 1452, he was never able to attend a higher school although his father, a lawyer, did later help him secure an apprenticeship with Andrea del Verrocchio, a famous painter based in Florence.

These were circumstances that made Leonardo’s thirst for knowledge all the greater – a thirst he endeavoured to quench by acquiring a large collection of books. He benefited from the invention of printing in Germany, "as he his exacly the same age as this invention" as well as a "man of epochal change", said Barbara Schneider-Kempf, Director of Berlin State Library at the exhibition opening.

Two German nationals – Arnold Pannartz and Konrad Sweynheym – subsequently brought book printing to Italy when Leonardo was twelve years old. They relocated their printing works from the Benedictine monastery of Subiaco to Rome In 1467. The next 30 years saw half a million books being printed in the Holy City alone. There were already 150 printing shops in Italy by the turn of the century.

The first books that Leonardo acquired were written in Italian – Latin texts only came later. Leonardo’s library also contained dictionaries and grammar books that bear witness to his efforts to learn Latin. He later wrote treatises for the fields painting, technology and science that dealt with the details of such subjects as anatomy, botany, mechanics, hydraulics and cosmology. “Leonardo, a Renaissance man par excellence, saw science as an art and art as a science,” said Alessandro Nova, Director at the Art History Institute of the Max Planck Society in Florence.

Not a solitary universal genius

Leonardo later claimed, not without irony and also not without a certain amount of pride, that as a ‘man without learning’ (omo sanza lettere), he himself had written at least 120 books. But none were ever published. His surviving records contain notebooks and thousands of sometimes loose pages that overflowed with sketches, calculations and handwritten remarks. Leonardo was left-handed, which may have been one of the reasons he wrote from right to left in mirror writing, and was always concerned with improving his writing.

We only know about his extensive library from his notes in which he meticulously recorded the volumes he had acquired. These notes are a treasure to art historians who have only recently been able to gain significant insights into them. “His library shows that he was by no means uneducated,” says Carlo Vecce, an expert on Leonardo and the literary scientist who, in conjunction with an international team, pioneered the research into Leonardo’s books. “His library creates the impression of a scholar, artist and scientist and reveals the close relationship he had with his books. He wasn’t a solitary universal genius but was engaged in lively exchanges with the culture of his time and with the famous authors of antiquity and the Renaissance, which Leonardo himself described as altori.”

Just one volume of Leonardo’s original library has survived, the Trattato di architettura e macchine by Francesco di Giorgio – a manuscript that has been annotated by the artist’s own hand and that is now kept at the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana in Florence. “Scientists have, however, been able reconstruct Leonardo’s treasure trove of books from manuscripts and the references they contain, such as quotations, authors and book titles, as well as from lists of the works in his possession,” said Paolo Galuzzi, Director at the Galileo Museum in Florence.

Leonardo listed a number of names, for example, in one of his notebooks in 1478, including Benedetto de l’Abaco, who taught the use of Arabic numerals, and Maestro Pagolo Medico, Paolo Toscanelli, a doctor, mathematician and important cartographer of his time. This was the cartographer who inspired Columbus to take the western route to India. “The names express Leonardo’s desire to gain access to mathematics and the world of scholars,” said Carlo Vecce. Another of Leonardo’s lists names another 98 books that include Aesop’s fables and Ovid’s Metamorphoses, works from the worlds of art, technology and medicine.

The exhibition: Leonardo's cosmos as a hall of mirrors

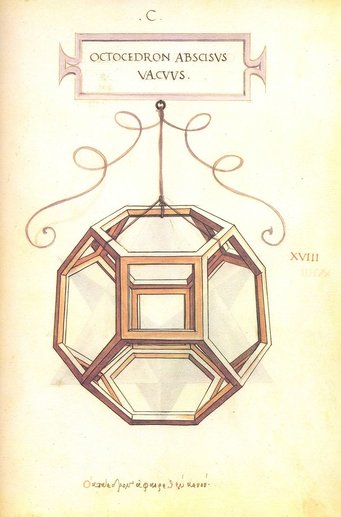

The exhibition "Leonardo's Intellectual Cosmos", which can be seen at the Berlin State Library from 11 May to 28 June 2021, now makes accessible for the first time a selection of the most significant texts that were in Leonardo's possession and were used by him. Added to this are numerous individual study sheets from Leonardo's hand as facsimiles. Since the original library is lost, the show brings together comparable contemporary editions of Leonardo's books made available by various Berlin libraries. Many works come from the Berlin State Library and the library of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science. Other loans came from the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin, the Planetarium and the Deutsches Technikmuseum Berlin, as reproductions of codices, works of art and objects such as printers' cabinets are also on display. For this purpose, Serge von Arx transformed the exhibition space into a circular hall of mirrors. The centre of the labyrinthine, staggered, colourfully illuminated glass elements is the sound installation "Knowledge Explosion" as a staging of Leonardo's manuscripts whirled up by the intellectual storm.

The computers that have been set up throughout the exhibition will allow visitors to browse through digitalized books and manuscripts and access information about the content of those books and how Leonardo used them. “The exhibition is providing a glimpse into the laboratory in Leonardo’s head, making it possible for visitors to track his continuous development as an artist and scientist,” said Jürgen Renn, director at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science. All the books that Leonardo possessed along with the respective tables of contents and links to the pages referencing the works in the artist’s notebooks will also be represented in the digital reproduction of the library.

The exhibition is accompanied by a comprehensive, richly illustrated catalogue containing essays by leading Leonardo experts. It is available in German and English from Giunti Editore. The exhibition is part of a cooperative research project on Leonardo da Vinci initiated by the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science for his 500th birthday in 2020.

BA