Mammals evolved big brains after big disasters

Largest study of its kind reveals the way relative brain size of mammals changed over the last 150 million years

The idea that comparing brain size to body size for any species provides a measure of the species' intelligence is one of the most deeply rooted paradigm in the life sciences. Although it's been popular for more than a hundred years, the paradigm bears fundamental assumptions on how brain size and body size co-evolve that have never been tested. Now, researchers from the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior have compared brain mass and body size of more than 1000 extinct and modern-day species—the largest database ever assembled for mammals. The findings reveal that most variation in brain size across species that live today can be explained by changes they underwent following cataclysmic events. It further highlights that brain size and body size have not always evolved in parallel. Given the complexity of species’ evolutionary history, the study urges a re-evaluation of the long-standing dogma that relative brain size can be equivocated with intelligence.

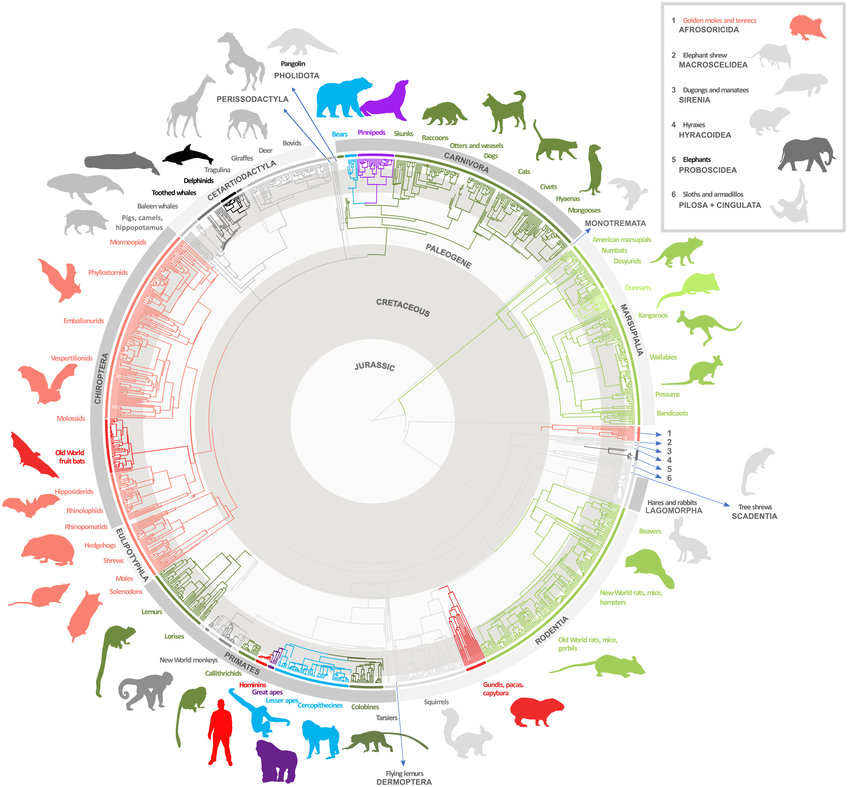

Scientists from Stony Brook University and the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior have pieced together a timeline of how brain and body size evolved in mammals over the last 150 million years. The international team of 22 scientists, including biologists, evolutionary statisticians, and anthropologists, compared the brain mass of 1400 living and extinct mammals. For the 107 fossils examined—among them ancient whales and the oldest Old World monkey skull ever found—they used endocranial volume data from skulls instead of brain mass data. The brain measurements were then analyzed along with body size to compare the scale of brain size to body size over deep evolutionary time.

The findings showed that brain size relative to body size—long considered an indicator of animal intelligence—has not followed a stable scale over evolutionary time. Famous “big-brained” humans, dolphins, and elephants, for example, attained their proportions in different ways. Elephants increased in body size, but surprisingly, even more in brain size. Dolphins, on the other hand, generally decreased their body size while increasing brain size. Great apes showed a wide variety of body sizes, with a general trend towards increases in brain and body size. In comparison, ancestral hominins, which represent the human line, showed a relative decrease in body size and increase in brain size compared to great apes.

Relative brain size is not always a measure for intelligence

The authors say that these complex patterns urge a re-evaluation of the deeply rooted paradigm that comparing brain size to body size for any species provides a measure of the species' intelligence. “At first sight, the importance of taking the evolutionary trajectory of body size into account may seem unimportant,” says Jeroen Smaers, an evolutionary biologist at Stony Brook University and first author on the study. “After all, many of the big-brained mammals such as elephants, dolphins, and great apes also have a high brain-to-body size. But this is not always the case. The California sea lion, for example, has a low relative brain size, which lies in contrast to their remarkable intelligence.”

By taking into account evolutionary history, the current study reveals that the California sea lion attained a low brain-to-body size because of the strong selective pressures on body size, most likely because aquatic carnivorans diversified into a semi-aquatic niche. In other words, they have a low relative brain size because of selection on increased body size, not because of selection on decreased brain size.

“We’ve overturned a long-standing dogma that relative brain size can be equivocated with intelligence,” says Kamran Safi, a research scientist at the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior and senior author on the study. “Sometimes, relatively big brains can be the end result of a gradual decrease in body size to suit a new habitat or way of moving—in other words, nothing to do with intelligence at all. Using relative brain size as a proxy for cognitive capacity must be set against an animal’s evolutionary history and the nuances in the way brain and body have changed over the tree of life.”

Disproportionate decrease in brain in small-brained mammals

Small-brained mammals, however, tell a different story. In contrast to the assortment of evolutionary paths taken by relatively big brained mammals, those near the bottom of the brain-body space, such as golden moles, marsupials, and bats, seem to follow a singular trajectory. “One of the surprising trends in smaller brained mammals is that they all show a disproportionate decrease in brain compared to body size, which indicates that there’s a limit to how small a body can be,” says bat biologist Dina Dechmann, a research scientist at the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior and co-author on the study, “For bats, which are the only truly flying mammals, this makes sense. Bats are energetically limited, and the brain is very costly to maintain and to carry around in flight. It seems like bats off loaded what they didn’t need.”

Two major events

The study further showed that most changes in brain size occurred after two cataclysmic events in Earth’s history: the mass extinction 66 million years ago and a climatic transition 23-33 million years ago. After the mass extinction event at the end of the Cretaceous period, the researchers noticed a dramatic shift in brain-body scaling in lineages such as rodents, bats and carnivorans as animals radiated into the empty niches left by extinct dinosaurs. Roughly 30 million years later, a cooling climate in the Late Paleogene led to more profound changes, with seals, bears, whales, and primates all undergoing evolutionary shifts in their brain and body size.

“A big surprise was that much of the variation in relative brain size of mammals that live today can be explained by changes that their ancestral lineages underwent following these cataclysmic events,” says Smaers. This includes evolution of the biggest mammalian brains, such as the dolphins, elephants, and great apes, which all evolved their extreme proportions after the climate change event 23-33 million years ago.

The authors conclude that efforts to truly capture the evolution of intelligence will require increased effort examining neuroanatomical features, such as brain regions known for higher cognitive processes. “Brain-to-body size is of course not independent of the evolution of intelligence,” says Smaers. “But it may actually be more indicative of more general adaptions to large scale environmental pressures that go beyond intelligence.”