Science's appeal against war

Otto Hahn and the Mainau Declaration of 1955

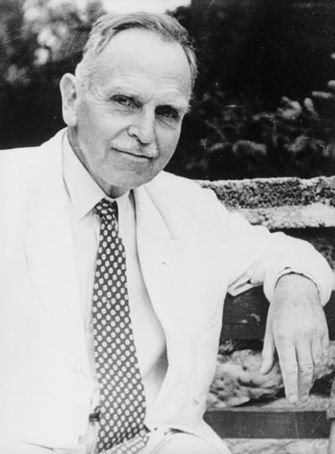

The first President of the Max Planck Society, Otto Hahn (1879-1968), is not only one of the most important researchers of the 20th century, but also among those scientists who, after WWII, campaigned massively against the threat of nuclear war and the arms race during the Cold War. As an organisation for basic research, the Max Planck Society is committed to Otto Hahn's legacy. In view of the current war situation in Ukraine, his appeals to use technology, science and research only for the good of humanity and against nuclear weapons are also a powerful warning for our times.

In 1938, Otto Hahn, together with his assistant Fritz Straßmann, had conducted an experiment at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry in Berlin that had led to the fission of uranium atomic nuclei. His research partner Lise Meitner provided the physical explanation for Hahn's unexpected discovery and his chemical measurements from her Swedish exile, together with Otto Robert Frisch. This was not only a milestone for atomic physics and radiochemistry, but also laid the foundation for the development of atomic weapons.

In 1938, Otto Hahn, together with his assistant Fritz Straßmann, had conducted an experiment at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry in Berlin that had led to the fission of uranium atomic nuclei. His research partner Lise Meitner provided the physical explanation for Hahn's unexpected discovery from her Swedish exile, together with Otto Robert Frisch. This was not only a milestone for atomic physics and radiochemistry, but also laid the foundation for the development of atomic weapons.

The driving force to advance this new discovery was the Second World War, which Germany unleashed with the invasion of Poland in September 1939, just one year after Hahn's discovery. The war escalated into a world war and motivated the USA to launch the Manhattan Project, in which it successfully pursued the scientific and technical development of an atomic bomb – not least with the help of Jewish researchers who had fled Nazi Germany.

When Germany surrendered in May 1945, the USA used the new bomb militarily for the first time in the fight against Japan. In August 1945, American bombers dropped a uranium bomb and a plutonium bomb on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The extent of the destruction resembled that of natural disasters. Added to this was radiation damage, which in this form created new horror scenarios.

Otto Hahn reacted to the news with deep dismay. At the time, he was a prisoner of war in Great Britain with other atomic researchers. After returning to Germany, Hahn became the founding President of the Max Planck Society in 1948, which had been established in West Germany from the ruins of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society. His personal distress at the devastating consequences of his discovery of nuclear fission led Hahn to commit himself to the preservation of peace and the renunciation of nuclear weapons.

The military use of atomic bombs in Japan was the beginning of the nuclear race of the superpowers, which was only de-escalated by Mikhail Gorbachev's policy and finally led to the fall of the Iron Curtain. Just four years after the Hiroshima bomb, the Soviet Union tested its first atomic bomb in 1949. In response, the USA developed a hydrogen bomb, which was tested in 1952 on Eniwetok Atoll in the Marshall Islands and whose explosive power was 500 times greater than that of the plutonium bomb on Nagasaki. The USSR had also developed the hydrogen bomb in the meantime.

Appeal from scientists in the Cold War

In view of these developments and the possibility of making the radiation damage of the hydrogen bomb even more massive by using a cobalt casing, Otto Hahn appealed to the politicians on both sides of the Iron Curtain in a major radio speech to stop the madness. On 13 February 1955, he read out his appeal "Cobalt 60 – danger or blessing for mankind?" on the radio, which broadcast it in Germany, Denmark and Norway. A few days later, the BBC invited Otto Hahn to read his lecture in English on their station as well.

In it, Hahn - influenced by the experience of the Hitler regime - sketched out the scenario of a Third World War and warned:

"An enormous responsibility lies in the hands of political leaders today. [...] A mentally ill or power-obsessed dictator could then [...] doom the civilised world, but with it also his own country, to radiation death. [...] Such a possibility must never occur, and hence the need for truly international control over the development of nuclear weapons, or better: peaceful coexistence of all peoples. [...] Today, war is no longer 'the continuation of politics by other means'. In a bomb war there are no longer victors and vanquished."

However, his hope that the "appeal of all responsible scientists who are aware of the dangers of using a means of war that threatens the world" could "bring those responsible for major policies [...] to a negotiating table [...]" remained unfulfilled.

Although Hahn's appeal was met with great public approval, the arms race expanded – from 1955 onwards also with the potentially active participation of the Federal Republic of Germany, which had regained its full sovereignty in May 1955. To lend weight to his appeal, Hahn initiated the Mainau Declaration at the Lindau Nobel Laureate Meeting in the summer of 1955. The signatories were the physicists Werner Heisenberg and Max Born, as well as 15 other German and international Nobel laureates. With ultimately 52 signatories worldwide, the declaration is the most powerful document of an appeal for peace by scientists. It states:

“With pleasure we have devoted our lives to the service of science. It is, we believe, a path to a happier life for people. We see with horror that this very science is giving mankind the means to destroy itself.

If war broke out among the great powers, who could guarantee that it would not develop into a deadly conflict? A nation that engages in a total war thus signals its own destruction and imperils the whole world.

Otto Hahn reacted to the news with deep dismay. At the time, he was a prisoner of war in Great Britain with other atomic researchers. A few weeks later, he received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his discovery. After returning to Germany, Hahn became the founding President of the Max Planck Society in 1948, which had been established in West Germany from the ruins of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society. His personal distress at the devastating consequences of his discovery of nuclear fission led Hahn to commit himself to the preservation of peace and the renunciation of nuclear weapons.

All nations must come to the decision to renounce force as a final resort. If they are not prepared to do this, they will cease to exist.“

As President of the Max Planck Society, Hahn actively promoted the peaceful coexistence of nations through science in the following years and helped in particular to establish diplomatic relations between Germany and Israel. In 1959, he was the first German to travel to Israel after the Second World War at the invitation of the Weizmann Institute, thus both reviving scientific exchange and initiating a normalisation in Germany's relations with Israel.

Today, the Max Planck Society has a network of researchers on all continents. Among the many cooperation projects are numerous valuable collaborations with colleagues from Russia, especially in the field of climate and environmental research.