Misperceptions about doctors’ trust in Covid-19 vaccines influence vaccination rate

Informing people about the strong positive consensus among doctors persistently leads to increases in Covid-19 vaccinations

How to increase vaccination rates by autumn, without any compulsion is shown by an international research team including the Max Planck Institute for Tax Law and Public Finance. They found that people’s willingness to get vaccinated is related to the presumed trust the medical doctors have in the vaccines. However, the study shows a large discrepancy between the assumptions of the population and the actual views of the medical profession.

For the study published in Nature, economists Vojtěch Bartoš, Michal Bauer, Jana Cahlíková and Julie Chytilová surveyed more than 9,600 medical doctors and a representative group of 2,100 people in the Czech Republic.

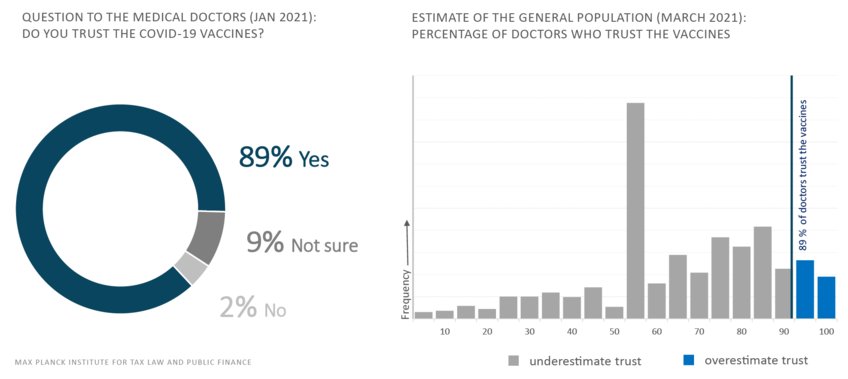

In January 2021, when the Covid-19 vaccines were not yet available to the general public, about 90 percent of the surveyed doctors stated that they trusted the vaccines, and planned to get vaccinated themselves. In contrast, most respondents from the general public assumed that this was true for only half of the doctors. Overall, 90 percent of the respondents underestimated how positive the medical community was about vaccines. Yet, as the researchers point out, there were not two conflicting groups, one believing in high and the other in low acceptance of Covid-19 vaccines among doctors. Four out of five of those surveyed assumed that the medical community was undecided. They estimated that the proportion of doctors who wanted to vaccinate themselves was only between 20 and 80 percent.

Unaware of medical doctors’ consensus

Co-author Jana Cahlíková from the Max Planck Institute for Tax Law and Public Finance sees a major reason for the misperception in the journalistic principle of balanced reporting: “This can lead to a minority opinion being given disproportionate weight in the reporting. This gives the public the feeling that the medical profession is undecided or controversial regarding the vaccines. Echo chambers’ or information bubbles at demos, in social networks or on the Internet can also trigger or reinforce this effect.”

It is obvious that such a distorted perception can lead to vaccination hesitancy. The researchers found that one’s own attitude towards vaccination is correlated with the assessment of how positive or negative the medical community is towards vaccines.

Dissolve misperceptions and increase vaccination rates

To find out whether the misperception can be corrected and, more importantly, whether the vaccination rate can be increased as a result, the research team carried out an experiment. They divided the subjects into two groups. One half was aware of the real views of the medical community, while the other half had not received any information. For the next nine months, the researchers monitored the respondents. Those participants who were informed about the actual opinions of the doctors not only changed their perception of the medical opinion, but also their willingness to be vaccinated changed persistently: the percentage of people who chose not to be vaccinated fell by 15-20 percent.

“As the vaccines became available to everybody a difference between the treatment and the control group started to emerge, with more people in the treatment group being vaccinated,” explains Cahlíková. Compared to other interventions that have been experimentally tested, learning about doctors’ opinion has proven to be effective and long-lasting.

“Our results suggest that contrasting views on controversial issues should be enriched with information about how prevalent such views are. In the case of Covid-19, for example, medical associations could help identify and communicate the individual views of the medical guild”, says Cahlíková.

The population’s trust in the medical community in the Czech Republic is comparable to other European countries. The researchers are therefore confident that the results can also be transferred to other countries, such as Germany.

“The inaccurate public perceptions that experts are divided, despite the fact that a broad consensus in fact exists, is very likely relevant in a number of other areas, such as the climate change debate, and it may undermine the societal support required to solve fundamental national and global problems,” adds Michal Bauer of the Center for Economic Research and Graduate Education – Economics Institute in Prague.