Language acquisition in multilingual children

Researchers studied the vocal experiences of children growing up on Malakula Island in Vanuatu where multilingualism is the norm

How children acquire their mother tongue has always fascinated scholars. However, for the most part, these studies have focused on children growing up with only one mother tongue, and mostly, in the United States learning English. Researchers of the Language Acquisition across Cultures Research Group at the Laboratory of Cognitive Sciences and Psycholinguistics of the Ecole Normale Supérieure and Heidi Colleran, leader of the BirthRites Research Group at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology (MPI-EVA), collaborated to study how children growing up in a multilingual society acquire language.

Language learning is a human universal. There is no human culture without language, and in every culture, children naturally pick up the language or languages used by those around them. Yet cultures and languages are extremely varied. How does our cognitive apparatus manage to adapt to multi-linguistic situations rather than just a monolingual one? So far, this question has remained unanswered, as very few studies have looked into truly multilingual populations and/or those outside the Global North.

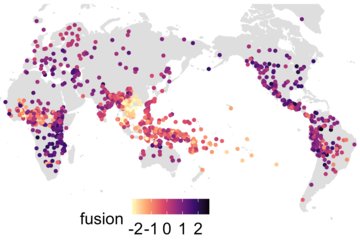

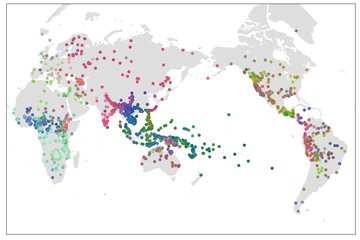

Heidi Colleran proposed to study the vocal experiences of the children of Malakula Island, in the archipelago of Vanuatu in the South Pacific, where multilingualism is the norm. She worked with families to collect naturalistic ‘long-form’ recordings of children’s speech environments as part of her long-term fieldwork on demography and culture on the island. Families from 11 different villages agreed to participate in this study, aware and proud of living on an island with the largest density of languages in the world – around 40 languages in a population of about 25,000 people. “A total of 38 children aged between five and 33 months representing 22 language varieties took part in our study,” says Alejandrina Cristia, leader of the Language Acquisition across Cultures Research Group. “According to their parents, these children regularly heard 2.6 languages on average, and up to eight different ones.”

USB recording device to go

To collect data, the team used a recording device the size of a USB key, which the children wore in a specially designed vest all day. This is a promising technique because it is very practical: it produces long duration recordings that represent well the children's everyday experiences without the interfering presence of a researcher. Its small size makes it a discreet tool, very quickly adopted by children and their social network who soon forget its existence. “Children wear the recording device directly on their clothing and are not limited in their movements,” says Cristia. “This is particularly important in cultures where children are looked after by several people throughout the day and where they have the freedom to go play with other children as soon as they can walk.”

As the length of the recordings makes transcription complex, the team has developed an automated analysis system, based on artificial intelligence, which identifies different types of voices: that of the target child, i.e. the one wearing the recorder, those of other children, as well as male and female adult voices.

“Data analysis revealed that children heard on average 11 minutes of speech per hour – about five minutes (31 percent) less than in previously studied monolingual populations”, says Heidi Colleran, leader of the BirthRites Research Group at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. “Nonetheless, children produced about as much and sometimes more speech in the multilingual as in the monolingual populations studied.” Intriguingly, the strongest association between the amount of speech heard and the amount of speech produced was with vocalisations by other children, rather than those made by adults. This points to the importance of children in language acquisition, and not just parents.

These results invite further research in populations that are under-represented in developmental science, and emphasize the need to take into account the diversity of languages, cultures and demographic structures when studying language acquisition in humans.

AC / SJ, HC