Looking into the heart of a stellar explosion

Max Planck researchers observe gamma-ray lines from a type Ia supernova

The extraordinary brightness and regularity of their light curves in the visible spectral range make type Ia supernovae valuable standardizable light sources, commonly used in modern cosmology. However, it has not yet been possible to directly measure these stellar explosions in their primary gamma radiation. Studies so far have been limited mainly to the outer layers of the supernova. With supernova SN2014J occurring early this year in the M82 starburst galaxy, researchers from the Max Planck Institutes for Astrophysics and for Extraterrestrial Physics in Garching succeeded for the first time in detecting gamma-ray lines. One of these studies even challenges the conventional theories for these types of explosions.

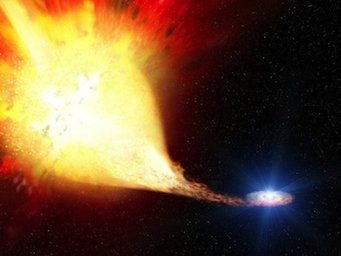

Before the big explosion: The artist’s impression shows a binary star system where mass is transferred from a companion to a white dwarf. As soon as sufficient matter has collected on the surface of the dwarf star, this can trigger a nuclear explosion which in turn ignites the catastrophic nuclear burning and destroys the white dwarf – a type Ia supernova flares up.

A type Ia supernova (SNIa) is commonly believed to be the thermonuclear explosion of a white dwarf star. These objects are the remnants of a normal star like our Sun in whose interior the fuel for nuclear fusion has been exhausted. A white dwarf ending as a supernova consists mainly of carbon and oxygen – the ashes left over from burning hydrogen and helium. If it is part of a binary system, it can be fed with matter from its companion. This eventually may lead to its catastrophic explosion, thus flaring up as a supernova.

In the course of this supernova, carbon and oxygen continue to fuse and produce huge quantities of a radioactive isotope of nickel (56Ni). The subsequent decay chain from nickel to cobalt and finally to iron generates large quantities of energy in the form of gamma-rays. These are reprocessed in the expanding material that is ejected by the explosion – i.e. converted into the visible radiation which makes the supernova shine for months. These supernovae are invaluable tools of modern cosmology as distance indicators.

Despite many observations and simulations, the detailed physics of a type Ia supernova is still disputed. Most models predict, among other things, that the material ejected is not transparent to gamma rays during at least the initial 10 to 20 days after the explosion. Later, more and more gamma-rays can escape, as the expanding supernova becomes increasingly transparent.

Chain reaction: The decay path 56Ni → 56Co → 56Fe releases large amounts of energy in the form of gamma-ray photons and positrons.

On 15 January 2014, a SNIa exploded in the M82 spiral galaxy, and was discovered only a few days later by S. J. Fossey and a team of students at University College, London. At a distance of slightly more than ten million light years, it was the nearest SNIa since at least four decades.

It therefore offered a good opportunity for observations, including those with the INTEGRAL gamma-ray observatory of the European Space Agency ESA. Only two weeks after SN2014J flared up, researchers of Roland Diehl’s Group at the Garching-based Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics discovered, with INTEGRAL, two characteristic gamma-ray lines which correspond to the radioactive decay of nickel (56Ni). The radioactive material must therefore have been near the surface of the explosion, otherwise the signal would not have been able to penetrate the supernova, and it would not have been possible to see it at such an early point in time.

This finding surprised the experts, as it indicates that the explosion did not ignite in the core of the white dwarf, but at its surface. “The signal is a mystery for us,” says Roland Diehl, principal author of a study published recently in Science. “But we could not find any mistakes. As is expected from radioactive decay, the gamma-ray lines of 56Ni became weaker within a few days and clearly came from the direction of the supernova.”

Diehl and his colleagues believe that their observation of the 56Ni gamma-rays provides new information on how the flow of matter from a companion star can ignite a white dwarf “from the outside”, as it were, hence without the need for the white dwarf to exceed a critical mass limit.

Satellite measurements: The spectrum of the type Ia supernova SN2014J observed by INTEGRAL 50 to 100 days after the explosion. Red and blue spots are data from the two instruments SPI and ISGRI/IBIS. The black curve depicts a comparison model for a supernova spectrum on day 75 after the explosion. The top row shows images in the three high-energy spectral bands of INTEGRAL. In all images, it is possible to clearly see a gamma-ray source at the (optical) position of SN2014J.

A second group also used INTEGRAL for a closer look at SN2014J: Scientists working with Eugene Churazov from the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics in Garching evaluated observations 50 to 100 days after the explosion. The team registered clearly the two brightest gamma-ray lines from the radioactive decay of a cobalt isotope (56Co) at 847 and 1238 kilo-electronvolts (keV). In addition, the flux at lower gamma-ray energies (200 to 400 keV) agreed with the theoretical predictions as well.

“The line fluxes indicate that an enormous quantity of radioactive nickel was synthesised in the explosion, more than half the mass of our Sun,” says Eugene Churazov, the principal author of a paper just published in Nature. “Both observed gamma-ray lines are clearly broadened by the Doppler effect.”

The researchers conclude from this that the cloud of radioactive material propagates with a speed of around 10,000 kilometres per second. Initially, the material is still so dense that the gamma-rays which originate from the radioactive decay of nickel to cobalt (with a typical timescale of nine days) lose a large portion of their energy.

The subsequent decay of cobalt to iron takes much longer, around 111 days. During this time, the ejected material becomes increasingly transparent so that gamma-rays can escape more and more, and thus turn the SNIa into a luminous source of characteristic 56Co gamma-rays after approximately three months.

Further comparisons with several conventional theoretical models which are based on exact computations of the nucleosynthesis processes during the explosion show good agreement between the SN2014J data and models for SNIa explosions, by which a white dwarf reaches its critical mass and explodes. Thus models where the white dwarf mass is significantly smaller than the critical limit, as well as pure explosion models, can already be excluded.

However, this is in contradiction to the above-mentioned early observation of gamma-ray lines from 56Ni. The interpretation derived from this would not require the white dwarf to exceed a limiting mass. Scientific discussion is continuing.

HAE / HOR