Black Holes are softly fed

Galactic mergers not the major feeding mechanism for mass monsters

A new study has obtained unexpected new insight into the feeding habits of the giant black holes, which are responsible for the emissions of some of the brightest objects in the universe: active galactic nuclei. Previous models had often assumed that mergers between galaxies are instrumental in driving matter into these black holes. But this systematic study of 1400 galaxies – the largest sample ever examined for the purpose – presents strong evidence that, at least for the past eight billion years, black holes have acquired their food more peacefully. (Astrophysical Journal, January 10, 2011)

The emissions of active galactic nuclei (AGN) are driven by matter falling into the galaxy's supermassive central black hole. But it is an open question in the physics of active galaxies how matter traverses the final hundreds of light-years to reach the immediate neighborhood of the black hole and be swallowed.

Following a study by David Sanders and collaborators from the late 1980s, most astronomers thought they had the answer: Mergers between galaxies of similar sizes (“major mergers”) would dramatically disturb the galaxies' gas, and make some of it fall towards the central black hole.

While this is a plausible scenario, only a systematic study can show whether or not this is indeed how giant black holes acquire their food. This is what Mauricio Cisternas and Knud Jahnke from the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy (MPIA) set out to do in 2008. Cisternas explains: “A study of this scope has become possible only recently, with the large surveys undertaken using the Hubble Space Telescope. Before, there was simply no way to examine sufficiently many active galaxies at large cosmic distances in sufficient detail.”

Cisternas and his collaborators obtained data for 140 active galactic nuclei (AGN), identified as such by X-ray observations from the XMM-Newton space telescope as part of the multi-wavelength survey COSMOS. Light from the most distant of these AGN has been traveling for almost 8 billion years to reach us: We see those AGN as they were 8 billion years ago, and the sample probes most of the black hole growth during the second half of cosmic history.

What makes this study special is the systematic way the astronomers selected a “control group” of ordinary galaxies without an active black hole – in other words, which do not have a black hole swallowing copious amounts of matter. For each of the AGNs in the study, nine non-active galaxies at roughly the same redshift, and thus roughly in the same stage of cosmic evolution, were selected from the same Hubble images, for a grand total of 1400 galaxies. This selection procedure allowed for a direct comparison between AGN and a matching population of ordinary, inactive galaxies.

The tell-tale sign that a galaxy has undergone a major merger over the past few hundred millions of years are distortions of its shape. For galaxies this distant, on images of the given resolution, a computerized, automatic identification of the degree of distortion cannot currently compete with visual inspection of the images by astronomers. Co-author Knud Jahnke (MPIA) says: “We were faced with the problem of bias. We knew that mergers were a plausible driver of AGN activity, so would we be more likely to classify AGN as distorted because of what we expected to find?”

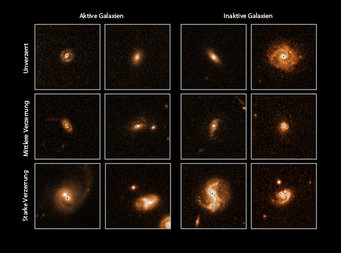

In order to eliminate possible bias, the researchers set up a blind study – standard operating procedure in fields like medicine or psychology, but unusual in astronomy. Cisternas removed tell-tale signs of galactic activity from the images so there would be no way to directly distinguish between the images of active and inactive galaxies.

The images were then given to ten galaxy experts based at eight different institutions, who were asked to judge each galaxy as “distorted” or “not distorted”. While their individual judgements showed significant variation, there was unanimity on the crucial question: None of the classifications showed a significant difference between AGN and inactive galaxies. There was no significant correlation between a galaxy's activity and its distortion, between its black hole being well-fed and its involvement in a major merger.

While mergers are a common phenomenon, and are thought to play a role at least for some AGN, the study shows that they provide neither a universal nor a dominant mechanism for feeding black holes. By the study's statistics, at least 75%, and possibly all of AGN activity over the last 8 billion years must have a different explanation. Possible ways of transporting matter towards a central black hole include instabilities of structures like a spiral galaxy's bar, the collisions of giant molecular clouds within the galaxy, or the fly-by of another galaxy that does not lead to a merger (“galactic harrassment”).

Could there still be a causal connection between mergers and activity in the more distant past? That is the next question the group is gearing up to address. Suitable data is bound to come from two ongoing observational programs (“Multi-Cycle Treasury Programs”) with the Hubble Space Telescope, as well as from observations by its successor, the James Webb Space Telescope, which is scheduled for launch after 2014.

(MP / HOR)