Look first

New light shed on the hierarchy of the senses by a study at the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics in Nijmegen

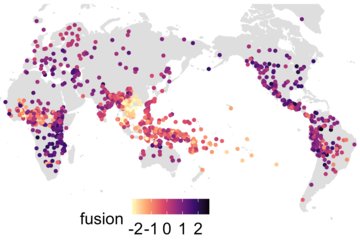

The material San Roque and her colleagues analysed was collected over a period of several years by the Institute’s scientists, who conducted field research around the globe. It includes major languages such as English and Italian, as well as languages spoken by relatively few people such as Chintang with its 4,000 speakers in Nepal and Whitesands spoken by only 7,500 people on the South Pacific island of Vanuatu.

“Thanks to the collaboration of speakers in various countries, we have managed over the years to collect unique material about daily life and language habits in a number of different cultures,” says San Roque, describing the significance of the data collection, which also serves as a basis for other linguistic studies by colleagues at the Institute. Not only were enough people recruited in Ghana, Italy, on the Malay Peninsula, in Papua New Guinea and in nine other countries who were willing to have audiovisual recordings of their daily chats made, but native speakers with expertise in transcription and translation were also available.

In their analysis of the collected material, San Roque and her colleagues counted how often the speakers used verbs in their everyday conversations that relate to any of the five senses and then determined the hierarchical position of each sense. They also recorded when such verbs are not used in direct reference to a sensory impression but in a figurative sense, as in the colloquial expression “we see eye to eye”.

The result of the study in Nijmegen confirmed one hypothesis proposed by the linguist Åke Viberg. In the early 1980s he had concluded from a large-scale study of more than 50 different languages that vision was the most important sense across languages. According to Viberg, vision ranks first and hearing ranks in second place, followed by the subordinate senses of touch, taste and smell.

When scientists deal with linguistic phenomena, their aim is not merely to take an inventory of vocabulary. Rather, they seek to address fundamental questions of human existence. After all, such studies deal with the relationship between speech, thought and reality and aim to increase our knowledge about how people perceive, experience, learn about and understand the world they live in. Thus, according to the Nijmegen-based linguists, it is possible that the preponderance of verbs expressing visual perceptions reflects broad principles of human experience and knowledge that are hardwired into the specific biology of the human sensory apparatus. This theory, which has been discussed by some linguists over the past decade or so, dovetails nicely with recent findings in the field of brain research, says San Roque. “It is estimated that 50 percent of the cortex is involved in visual functions.”

However, San Roque, Kendrick, Norcliffe, and Majid also believe other explanations are plausible as well. It may be that people around the world most frequently talk about visual perceptions simply because there are more opportunities for visual experiences than, for example, taste experiences. After all, you can see a great deal, but you can’t go around tasting everything.

Although their findings support the hypothesis of visual dominance as a universal characteristic of all languages, they found no evidence of a fixed hierarchy of the other four senses, in contrast to the previous claims.

Hearing ranked second in most of the languages studied, but there were exceptions to this rule. In Semai, for example, which belongs to the Aslian language family and is spoken by some people on the Malay Peninsula, verbal references to olfactory impressions occur more frequently than allusions to hearing. “These results are consistent with previous studies reporting the key role of smell in some societies,” says Majid. Olfactory perceptions also figure more prominently in Jahai and Maniq, languages related to Semai, than in most other languages. The Jahai and Maniq, hunter-gatherer groups in southern Thailand and Malaysia, have around a dozen different abstract terms to describe odours, as Majid and colleagues have reported previously.

San Roque and her colleagues were also unable to observe a fixed hierarchy of the other senses. For example, verbs referring to tactile sensations rank in third place in languages such as Whitesands, Avatime and Mandarin. In Cha’palaa and Duna, by contrast, smell ranks third, while in Italian and Spanish third place is occupied by taste.

For the Nijmegen-based researchers, these results are an indication that human language usage is both a product of biological inheritance and a product of a specific culture.

BF/SB