Cellular power outage

Scientists are discovering pathways for proteins that lead defective proteins to the mitochondria for quality control

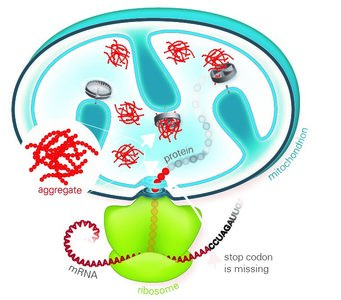

A common feature of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's, Parkinson's or Huntington's disease are deposits of aggregated proteins in the patient's cells that cause damage to cellular functions. Scientists at the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry and Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität in Munich report that, even in normal cells, aberrant aggregation-prone proteins are continually produced due to partial failure of the respiratory system. Unless they are removed by degradation, aggregates accumulate preferentially in the mitochondria, the cellular power plants, ultimately blocking energy production. In order to get rid of these toxic aggregates, cells have developed an elaborate protein quality control system.

Misfolded proteins made from defective blueprints are often sticky and clump together. Accumulation of such faulty proteins is known to contribute to the progression of several diseases. Therefore, cells have internal quality control mechanisms that detect and rapidly destroy faulty proteins. Proteins are produced by ribosomes, and misfolding can occur if they stall while decoding a damaged template. If the necessary ribosome-associated quality control machinery (RQC) does not function properly, defective proteins accumulate and form toxic aggregates in the cytoplasm of the cells. A previous study reported that this aggregation mechanism is mediated by so-called CAT-tails – C-terminal alanine-threonine sequences that are added to the defective proteins. So far, studies have focused on how the RQC recognizes and clears blocked ribosomes in the cytosol. The collaborating groups at the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry and the university have now investigated the clearance of ribosome-blocked proteins destined for the mitochondria.

Mitochondria are the cell’s power plants, converting the energy from nutrients into ATP. ATP is the universal “energy carrier” and is essential for all processes in living cells. Damage to the mitochondria thus has fatal consequences for cells. Their dysfunction not only plays a role in the development of metabolic diseases such as diabetes, but also in neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's, Parkinson's or Huntington's disease. "This is why the mitochondria are also referred to as the 'Achilles' heel' of the cell," says Walter Neupert from the Department of Cell Biology at the Biomedical Center of the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität. Neupert and his team have been studying mitochondria for a long time. They discovered that even normal, unstressed cells continually produce faulty proteins under respiratory conditions. Apparently, a side reaction in the respiratory system in the mitochondria causes them to steadily release reactive oxygen species that can damage DNA, RNA and proteins. To determine how aggregates can arise in mitochondria and cause damage to cells, they cooperated with the team led by F.-Ulrich Hartl at the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry. Hartl has been investigating protein aggregates, a cellular cause of neurodegenerative diseases, for many years.

Faulty proteins inside mitochondria

“CAT-tailed proteins have a particularly toxic effect on mitochondrial function. Once CAT-tailed proteins are imported into the mitochondria, they form aggregates that may act as a seed, and ultimately bind proteins free of defects that have vital roles for the cell” explains Toshiaki Izawa, first author of the study, together with Sae-Hun Park. Among the latter are the mitochondrial chaperones and proteases, which – once clumped – can no longer efficiently perform their normal function of repairing the damaged proteins and eliminating faulty proteins. A vicious cycle begins, and eventually such aggregates can damage the molecular power plants and shut down ATP production.

The mitoRQC pathway

“The elimination by the degradation machinery in the cytoplasm of mitochondrial proteins that have been marked as faulty by the attachment of CAT-tails is tricky. The synthesis of these proteins in the cytosol is tightly coupled to their import into the mitochondria. Therefore, cells have developed another strategy to get rid of faulty mitochondrial proteins and maintain cellular homeostasis”, says Park. “We identified the cytosolic protein Vms1 as a key component of a novel pathway termed mitoRQC that protects mitochondria from the toxic effects of such aberrant proteins”, explain the authors of the study. Vms1 suppresses these toxic effects by reducing CAT-tailing of ribosome-stalled polypeptides, thereby preventing aggregation and directing aberrant polypeptides to intra-mitochondrial quality control systems. “Our results suggest a way in which mitochondrial toxicity may contribute to neurodegenerative diseases. These findings provide important novel insights into the mechanisms of cellular protein quality control as well as disease progression” Hartl concludes.

SiM/HR