Starlink satellite electronics interfere with radio telescopes

Satellite operator SpaceX cooperates with radio astronomy

Just like us, using mobile phones, satellites also communicate with each other and with receiving stations on Earth using radio waves. Ideally, however, elaborate agreements with Network Agencies prevent satellites to interfere with radio astronomy observatories. An exception that has not been researched so far is the interference radiation that emanates from the on-board electronics of certain satellites, for exmple the Starlink satellite constellation of SpaceX.

Scientists from a number of leading research institutions including the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy in Bonn, Germany, used the Low Frequency Array (Lofar) telescope to observe 68 of SpaceX’s satellites. The authors conclude that they detected “unintended electromagnetic radiation” emanating from onboard electronics. This is different from communications transmissions, which had been the primary focus for radio astronomers so far. The unintended radiation could impact astronomical research. They encourage satellite operators and regulators to consider this impact on radio astronomy in spacecraft development and regulatory processes alike.

Millions of times weaker than a mobile phone on the moon

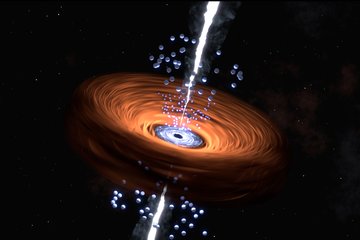

The radio signals that astronomers receive from space are usually very weak. Mesuring instruments perceive radio-waves caused by humans as much more intense than the radiation from astronomical objects that propagates through space and hits the Earth. Prominent sources of cosmic radio-waves include shocked remnants from past stellar explosions or matter ejected from the vicinity of supermassive black holes. Even though these are among the most intense energy sources in the universe, their great distance from the Earth makes for low signal strengths. If an astronaut on the moon had an average mobile phone with him or her, it would be measurable with terrestrial radio telescopes. The intensity of that signal would correspond to the brightest astronomical radio sources in the sky. For this reason, radio telescopes are preferably shielded from terrestrial interference radiation.

A new challenge arises from the expansion of huge satellite constellations such as SpaceX's Starlink satellite network. In order to supply even remote regions of the Earth with broadband internet, thousands of individual satellites must orbit close to Earth. This also means that a radio telescope has many satellites in view at all times. To prevent the satellites from interfering with observations by radio astronomers while they are communicating with their ground stations, frequency bands that are particularly important for astronomy are protected. However, the radiation from the Starlink satellites, which has now been observed for the first time, has not been recorded so far. Most likely, it is due to electromagnetic leakage radiation from the on-board electronics. Although this radiation has only a very low power in the range of a few microwatts and is about a million times weaker than that of a mobile phone, it is comparable to or even stronger than the radiation measured by radio observatories from space due to the short distance to Earth.

“This study represents the latest effort to better understand satellite constellations’ impact on radio astronomy,” said Federico Di Vruno. Di Vruno is the co-director of the International Astronomical Union’s Centre for the Protection of the Dark and Quiet Sky from Satellite Constellation Interference. This organisation seeks to coordinate the interests of astronomy with those of space agencies, industry and regulators worldwide. Dr Vruno is also a spectrum manager for the SKA Observatory that is currently under construction.

When satellite constellations become a problem

Di Vruno and his team initially focused on SpaceX satellites because SpaceX had the largest number of satellites - more than 2,000 - in orbit at the time of the observations. Specifically, this study observed 68 satellites passing through the field of view of the Lofar radio telescope during a one-hour observation window. For 47 of them, Lofar detected previously unknown spurious radiation in the frequency range between 110 and 188 megahertz. SpaceX is nevertheless not violating any rules, as for satellites, this kind of radiation is not covered by any international regulation.

The authors recognize that SpaceX is not the only operator of large satellite constellations and they expect to detect similar unintended emissions from other low-Earth-orbiting satellites. While corresponding measurements are already planned, simulations already show that the larger the satellite constellation, the stronger the received leakage radiation. This is because the signal measured by the radio telescopes is a superposition of the contributions from all satellites transmitting in the observatory's catchment area. “This makes us not only worried about the existing constellations, but even more about the planned ones. And also about the absence of clear regulation that protects the radio astronomy bands from unintended radiation”, says Benjamin Winkel from the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy in Germany.

Solutions through cooperation

The authors are in close contact with SpaceX, and the company has offered to continue to discuss possible ways to mitigate any adverse effects to astronomy in good faith. As part of their design iteration, SpaceX has already introduced changes to its next generation of satellites which could mitigate the impact of these unintended emissions on important astronomical projects. The early recognition of the problem provides the necessary time to work together on technical solutions and to hold the necessary discussions with the regulatory authorities.

Despite the as yet unforeseeable side effects on astronomy, Michael Kramer, Director at the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy and President of the Astronomical Society in Germany, welcomes SpaceX's cooperative approach: "With SpaceX setting an example, we are now hoping for the broad support from the whole satellite industry and regulators."

NJ/TB