Handier than Homo habilis?

The versatile hand of Australopithecus sediba makes a better candidate for an early tool-making hominin than the hand of Homo habilis

Hand bones from a single individual with a clear taxonomic affiliation are scarce in the hominin fossil record, which has hampered understanding of the evolution of manipulative abilities in hominins. An international team of researchers including Tracy Kivell of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany has now published a study that describes the earliest, most complete fossil hominin hand post-dating the appearance of stone tools in the archaeological record, the hand of a 1.98-million-year-old Australopithecus sediba from Malapa, South Africa. The researchers found that Au. sediba used its hand for arboreal locomotion but was also capable of human-like precision grips, a prerequisite for tool-making. Furthermore, the Au. sediba hand makes a better candidate for an early tool-making hominin hand than the Homo habilis hand, and may well have been a predecessor from which the later Homo hand evolved.

The extraordinary manipulative skills of the human hand are viewed as a hallmark of humanity. Over the course of human evolution, the hand was freed from the constraints of locomotion and has evolved primarily for manipulation, including tool-use and eventually tool-production. Understanding this functional evolution has been hindered by the rarity of relatively complete hand skeletons that can be reliably assigned to a given taxon based on a clear association with craniodental fossils.

Tracy Kivell of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany and colleagues from the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa, Duke University in Durham, USA and the University of Zurich in Zurich, Switzerland, now describe the earliest, most complete fossil hominin hand post-dating the appearance of stone tools in the archaeological record around 2.6 million years ago. The fossil remains of an adult female Au. sediba from Malapa, South Africa, include an almost complete right hand in association with the right forelimb bones, in addition to several bones from the left hand. “Almost all other fossil hominin hand bones prior to Neandertals are isolated bones that are not anatomically associated (i.e., do not belong to the same individual) and are not clearly attributed to a specific hominin species”, says Kivell: “The Australopithecus sediba hand thus allows us for the first time prior to Neandertals to evaluate the functional morphology of the hand overall, rather than just from isolated bones.”

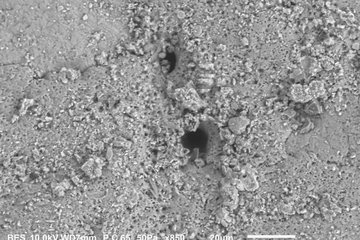

The researchers reconstructed the Au. sediba hand, then compared it with other hominin fossils and investigated the presence of several features that have been associated with human-like precision grip and the ability to make stone tools. They found that Au. sediba has many of these features, including a relatively long thumb compared to the fingers – longer than even that of modern humans – that would facilitate thumb-to-finger precision grips. Importantly, Au. sediba has more features related to tool-making than the 1.75-million-year-old “OH 7 hand” that was used to originally define the “handy man” species, Homo habilis. However, Au. sediba also retains morphology that suggests the hand was still capable of powerful flexion needed for climbing in trees.

“Taken together, we conclude that mosaic morphology of Au. sediba had a hand still used for arboreal locomotion but was also capable of human-like precision grips”, says Kivell and adds: “In comparison with the hand of Homo habilis, Au. sediba makes a better candidate for an early tool-making hominin hand and the condition from which the later Homo hand evolved.”