Giant memory thanks to tiny capacitors

German-Korean research team produces a permanent memory using a new procedure and thereby sets a memory density record

The electronics of the future are becoming increasingly smaller and lighter, as well as faster and more powerful. A method now developed by scientists at the Max Planck Institute of Microstructure Physics in Germany, Pohang University of Science and Technology (POSTECH) in Korea and the Korea Research Institute of Standards and Science (KRISS) may help to achieve these goals. The new method enables the production of particularly densely-packed moemory storage. Using an extremely finely perforated mask, the researchers housed capacitors made out of platinum and lead-zirconate-titanate (PZT) with a density of 176 billion bits on a square inch - a world record for this material. Such storage is easy to control and can save memory permanently. Chips made from this material could therefore replace current working memories in which saved bits have to be constantly refreshed. (Nature Nanotechnology Advance Online Publication, June 15, 2008, doi:10.1038/nnano.2008.161)

Whether MP3 players, camera mobile phones, navigation systems or notebooks, all have to be compact but also able to store increasing large amounts of music, images, films or maps, and process them quickly. Innovative new memory would contribute greatly towards making electronics smaller and more powerful, especially if it were able to save information permanently, but still process data as quickly as the DRAMs on which computers currently store programs. "Permanent memory of this kind can be produced very simply and efficiently using our methods," said Dietrich Hesse, a scientist at the Max Planck Institute of Microstructure Physics in Halle, Germany, who played a prominent role in the work of the research team.

The permanent memory produced through the German-Korean cooperation can save 176 billion bits per square inch, which is 27 billion bits per square centimeter - more than any comparable memory made of this type of material. "We are approaching memory density of several terabits or billions of bits per square inch, and we hope to be able to increase the memory density even further," relates Dietrich Hesse. Such high memory density is necessary for more widespread use of permanent memory. They could, for example, make the hard-drive and tedious booting up of computers a thing of the past. The nano-capacitors meet a further requirement for memory application: scientists can control each memory precisely, even though they are only 60 nanometers apart from one another. "This work shows that unconventional and previously overlooked production methods from associated fields in electronics research can mean significant progress in the search for high-density, solid-state memory," explains Professor Ulrich Gösele, Director at the Max Planck Institute of Microstructure Physics.

The memory’s exceptional performance is a result of the principle on which they are based, as well as precision production: the ceramic material lead-zirconate-titanate is ferroelectric. In this type of material, all unit cells, the smallest parts of a crystal, have permanent electrical dipoles. These are comparable with magnetic dipoles in iron from which they take their name. Like the north and south pole of a magnet, the positive and negative poles of a permanent electrical dipole can be interchanged - but much more quickly. This material can therefore save data permanently like a hard-drive, but processes it as quickly as a working memory. Lead-zirconate-titanate allows a titanion to be moved into the unit cell using an external electrical field at temperatures under 460 degrees Celsius. Above this temperature, the dipole constantly changes direction without external intervention.

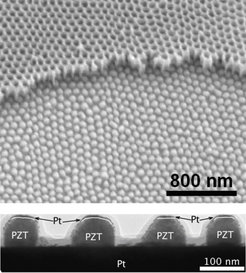

The scientists then produced a 100 nm thin perforated mask made of aluminum oxide in order to house 176 billion capacitors made of this ferroelectric material on a square inch. To do this, they electrochemically oxidized an aluminum film, a method known as the Eloxal process, which has been used for decades to provide aluminum components with a protective coating and to give aluminum tableware and even some MP3 players a matt-metallic sheen. In this process, pores generally eat into the aluminum oxide in a random pattern. However, by carefully selecting the temperature, PH level and chemical composition during oxidation, the researchers forced the pores into a hexagonal arrangement where each pore is surrounded by six others. The hexagonal pattern though is distorted in some places, which makes it unusable as a mask for a memory. "If we shape the aluminum with a punch beforehand, the pores arrange themselves in a completely regular pattern," says Woo Lee of KRISS. The punch contains billions of points that leave an equal number of indentations in the aluminum. These indentations also help oxidation, providing the pores with a starting point to eat into the material.

Even with the finely perforated mask, the process is still incomplete. The Halle-based scientists placed the mask on a magnesium-oxide plate heated to 650 degrees Celsius. This plate is coated with platinum and serves as a support. They then vaporized it with a laser beam in a perfectly balanced PZT ratio until the ceramic has deposited 30 to 50 nanometers on the platinum. A thin platinum cover completes the capacitors in which the precious metal layer serve as electrodes and the ceramic serves as dielectric material. "We could, in principle, also use other materials for the electrodes," said Dietrich Hesse. Removing the thin masks did not present an insurmountable obstacle either. In doing so, the scientists must be careful that it does not break, leaving a part of it on the memory. With a high degree of skill and a piece of scotch tape, they easily managed to remove the mask. "Remarkably, the individual sandwiches made of platinum and PZT do not get caught in the pores," explains Dietrich Hesse adding, "Presumably, the capacitors that we heat to 650 degrees Celsius contract when cooling down before we remove the mask at room temperature."

The success of this project is also due to the fruitful German-Korean cooperation. "The unbureaucratic, close teamwork with the Korean scientists, who contributed their respective capabilities, experience and methods to the work, has paid off handsomely in this case," said Ulrich Gösele.

This project was supported by the Max Planck Society, the Volkswagen Foundation, the German Research Foundation, the Korea Research Foundation and the "Brain Korea 21" program".