A solar eclipse sheds light on physics

Text: Helmut Hornung

Two great scientists in discussion: During the total solar eclipse of 29 May 1919, Sir Arthur Eddington (right) confirmed Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity by determining the deflection of the starlight next to the Sun. The photo of the two researchers was taken in 1930 at the University of Cambridge in Great Britain.

On 25 November 1915, Albert Einstein published an article of only three pages and thereby put the finishing touches to a construct of ideas which viewed gravity in a new light. In his Special Theory of Relativity, which he had developed ten years previously, the then 26-year-old physicist had found out that the measured length of an object and the duration of a process depend on how the observer moves relative to the event. In addition, Einstein postulated, as a consequence of this, the equivalence of mass and energy: each can be converted into the other.

The Special Theory of Relativity applies solely to systems which are in uniform motion. Einstein now expanded his thoughts to accelerated motion and included gravitation. He combined space and time to a four-dimensional, curved space-time and concluded that gravity determines the geometry of this space-time.

An example serves to illustrate the crucial statement of the General Theory of Relativity: Imagine a mattress which is not very firm. If we put a bowling ball onto the mattress, it will form a deep well. A marble now allowed to roll past this well will not continue on a straight path, but move in a curve at the edge of the well. If the marble has not been sent on its way with enough speed, it will roll towards the bowling ball and finally come to rest in the well.

Light on a crooked path: A large mass – the Sun, for example – deflects the light of a distant star which passes close by. An observer on Earth therefore sees the star in a different position. This shift is tiny in reality, but can be measured during a total eclipse of the Sun.

Let us now transfer the experiment to the universe: the mattress is space-time, the bowling ball our Sun and the marble a planet. According to Einstein, the planets are not attracted by the Sun, but rather move along the curvature caused by the indentation in space-time brought about by the huge mass of the Sun.

Albert Einstein himself recognized very early on that this type of curved trajectory applied not only to planets and large celestial bodies in motion. Light beams should also travel on curved paths in a gravitational field. Einstein was by no means the first to ask himself how light reacts to large masses, however. In 1783, the English scholar and clergyman John Mitchell claimed that light – which according to Isaac Newton should consist of tiny corpuscles – does not always travel in straight lines, but can be deflected by the gravitational force of a body.

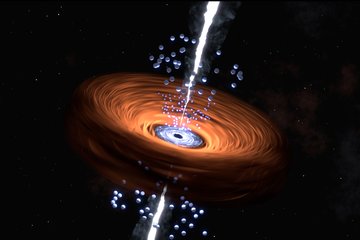

Mitchell even went one step further. He described a giant star whose gravitation was so great that the light particles emitted by the star would fall back onto its surface. The natural philosopher thus ultimately described an object which we today call a black hole.

Directorship in the attic: In October 1917, the Kaiser-Wilhelm Institute for Physics officially started its work in Berlin under the leadership of Albert Einstein – albeit not in a spacious building, but in the flat of its famous director. Einstein headed this unusual Institute for five years.

Towards the end of the 18th century, the French mathematician Pierre-Simon Laplace also described - independently from Mitchell - bodies whose attractive force was to be so strong that no light could escape from their surfaces. Laplace calculated such an object and found that the total mass of the Sun would have to be contracted to a sphere six kilometres in diameter.

Finally, in 1801, Johann Georg von Soldner, who later became the director of the Munich observatory in Bogenhausen, published an essay entitled “The deflection of a light ray from its rectilinear motion, by the attraction of a celestial body at which it nearly passes by”. Von Soldner calculated by how much the apparent position of a distant star would shift in the sky if its light passed close to the Sun. He arrived at a value of 0.875 arc seconds – an angle at which a 1 euro coin would appear from a distance of five kilometres.

Although Albert Einstein was not aware of the deliberations of the Munich astronomer, he was also working on the problem of light deflection by the Sun around 1911. His calculations actually resulted in a value of 0.83 arc seconds – very close to what von Soldner had detected. Einstein proposed testing the theory on reality, namely measuring the apparent deviation during a total eclipse of the sun.

Black Sun: On 29 May 1919, the new moon covered the blazingly bright disk of the Sun. The astronomers back then were already able to quite impressively photograph the shadow dance. This historical photo clearly shows the corona, the outer gas atmosphere of the Sun.

The next spectacle of this kind took place in 1912 over Brazil, but was literally a washout due to the weather. The eclipse on 21 August 1914 occurred over Russia three weeks after the outbreak of the First Word War. While a German expedition headed by Erwin Freundlich was captured and interned by the Russians, the American astronomers headed by William Campbell were met with a cloud-covered sky south of Kiev instead of the natural spectacle.

Therefore, the measurements came to nothing – and incidentally, their results would certainly not have pleased Einstein. The reason being that as he further advanced his work to the General Theory of Relativity over the next few years, he discovered the relationship between gravity and space curvature described above. This should give rise to an effect which had to be added to the pure deflection caused by gravity. In a nutshell: the shift in the star’s position at the periphery of the Sun doubled to 1.75 arc seconds. Einstein published this value as part of his essay “The Foundation of the General Theory of Relativity”, which appeared in May 1916 in Annalen der Physik.

The scientists thus waited for the next opportunity to test the prediction. Should it prove to be correct, the new theory would have passed its first test with flying colours. The opportunity arrived on 29 May 1919. The astronomers determined the perfect observation sites to be the Island of Principe off the coast of Spanish Guinea and the village of Sobral in the north of Brazil.

One thing was remarkable: it was English researchers who prepared two expeditions while the First World War was still raging in order to confirm the theory of a German professor. Albert Einstein had been the Director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics since 1917 at the instigation of Max Planck, although the new Institute initially consisted only of Einstein’s study in an attic above his flat in Berlin-Schöneberg. Only five years later, in October 1922, Einstein left Germany owing to death threats and transferred his directorship to Max von Laue.

Six months before the total solar eclipse, the astronomers took photographs of the region in the sky where the darkened Sun was to be observed on 29 May 1919. It turned out to be a stroke of luck that the Sun would then be in the brightly shining star cluster known as the Hyades and the individual stars should be clearly visible close to the Sun. The scientists were nevertheless faced with a difficult task.

The calculated 1.75 arc seconds apply only for the case where the star is directly at the periphery of the Sun. At a distance of two solar radii, the angle shrinks to 0.6 arc seconds. Even a shift of one arc second is imaged on the glass photographic plate as a distance of only 0.026 millimetres by the telescope used by the expedition on the island of Principe! In addition, the ever present air turbulence distorts the image of the star, and the refraction in the atmosphere plays its part as well.

On 8 March 1919, two expeditions started out from England, one destined for the island of Principe, the other for Sobral. Arthur Eddington, the famous scientist and secretary of the Royal Astronomical Society, coordinated the two teams: Eddington himself had set up his camp in a coconut plantation on Principe on the day of the eclipse – and in the morning heavy rain began to fall there. It was only towards midday, during the eclipse, that the clouds parted repeatedly for a few seconds. The astronomers took 16 photographs, of which only two were usable. The researchers in Andrew Crommelin’s team in Sobral had more luck; they succeeded in taking eight suitable photographs.

Back in England, Eddington evaluated the plates and announced the preliminary result at a meeting in Bournemouth at the beginning of September 1919. On 6 November, Crommelin presented the final result at a joint meeting of the Royal Society and Royal Astronomical Society: the deviation at the periphery of the sun amounted to 1.98 +/- 0.18 arc seconds for one telescope, and 1.60 +/- 0.31 arc seconds for the other.

“Lights All Askew in the Heavens”: This was the headline of an article in the New York Times of 10 November 1919 about the confirmation of the General Theory of Relativity.

Since doubts had repeatedly been expressed about the accuracy of these values, Eddington’s photographic plates were re-measured with modern instruments in 1979 at the Royal Greenwich Observatory. The result: 1.90 +/- 0.11 arc seconds. The General Theory of Relativity had passed its first test with flying colours!

On 7 November 1919, the London Times titled one of its articles “Revolution in Science: New Theory of the Universe. Newtonian Ideas Overthrown.” And the New York Times also wrote on its front page of 10 November: “Lights All Askew in the Heavens.” In contrast to the enthusiastic reception shown by the foreign press, the media in Germany were more reticent on the subject. Not until 14 December 1919 did the Berliner Illustrierte Zeitung publish a photo of Einstein and an article entitled: “A new luminary for the history of the world: Albert Einstein, whose research means a total revolution in the way we see the world and whose findings are equal to those of a Copernicus, Kepler and Newton”.

The physicist, who became famous overnight, found the fuss about his person annoying. He was said to have dreamed of a postman, who – in the form of a devil – constantly brought him new letters, although he had not yet answered the earlier ones. And he wrote to his colleague Max Born: “It is so awful here that I can hardly breathe, let alone do any proper work.”