Why nerve cells die

Protein aggregates in cytoplasm interfere with important transport routes

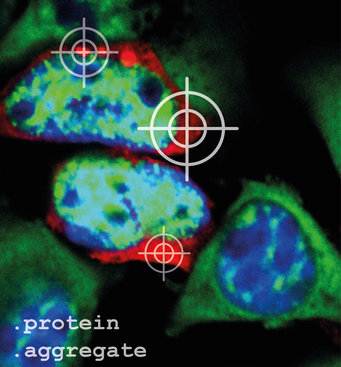

In the brains of patients with neurodegenerative diseases, medical researchers can observe protein deposits, also called aggregates. For many years, these aggregates have been suspected to contribute to the death of nerve cells, and to diseases like Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, or Huntington's. Scientists from the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry in Martinsried, led by Mark Hipp and Ulrich Hartl, have now shown that the location of protein aggregates strongly influences the survival of cells. While aggregates within the nucleus barely influence cellular function, deposits of identical proteins within the cytoplasm interfere with important transport routes between the nucleus and the cytoplasm. This results in a blockage of protein and RNA transport into and out of the nucleus. In the long run this can lead to the death of the affected cells, and progression of the disease. The results of these studies have now been published in the journal Science.

Proteins consist of long chains of amino acids and function in cells like small machines. To be able to fulfill their function proteins have to assume a predetermined three-dimensional structure. In healthy cells there is a large variety of folding helpers and extensive quality control machinery. Misfolded proteins are either repaired or rapidly degraded. If this occurs inadequately, or not at all, proteins will clump together, form aggregates and harm the cell.

Protein aggregates are associated with many neurodegenerative diseases including ALS, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and Huntington’s Disease. How exactly aggregates harm cells is however still unknown. In 2013 several groups in Martinsried formed the ToPAG consortium to address this question, and can now report their first success. Scientists in the lab of Prof. Hartl, a world-renowned expert on protein folding, have demonstrated that the location of the aggregates determines the fate of the nerve cells.

Together with Konstanze Winklhofer and Jörg Tatzelt from the Ruhr-University Bochum, the researchers have expressed artificial aggregation prone proteins as well as Huntington’s disease-causing mutants of the protein huntingtin in cultured cells. Both types of protein accumulate in large protein deposits. “It came as a big surprise to us that the direction of the proteins to the cytoplasm instead of the nucleus resulted in more soluble, but also more toxic aggregates”, says Mark Hipp, a group leader in the department of Ulrich Hartl and leader of the study. The protein deposits in the cytoplasm blocked the transport of RNA and correctly folded proteins between the nucleus and the cytoplasm. It seems that the sticky surfaces of the aggregates can sequester important proteins and thereby inactivate them. “We have detected multiple components of the cellular transport machinery inside the aggregates. This results in the depletion of these factors from the cell, and, like a machine with missing parts, the cell is then unable to function properly”, explains Andreas Woerner the first author of the study. Once the blueprint for all proteins, the RNA, is trapped within the nucleus, protein synthesis cannot progress, and the cells deteriorate. It is not completely clear why the nuclear aggregates are less harmful, but the researchers have evidence that the nuclear protein NPM1 plays a central role in shielding these aggregates.

“The results of this study bring us researchers and physicians one big step further”, summarizes Mark Hipp. “Only if we understand how aggregates damage cells is it possible to develop appropriate countermeasures in the future.”